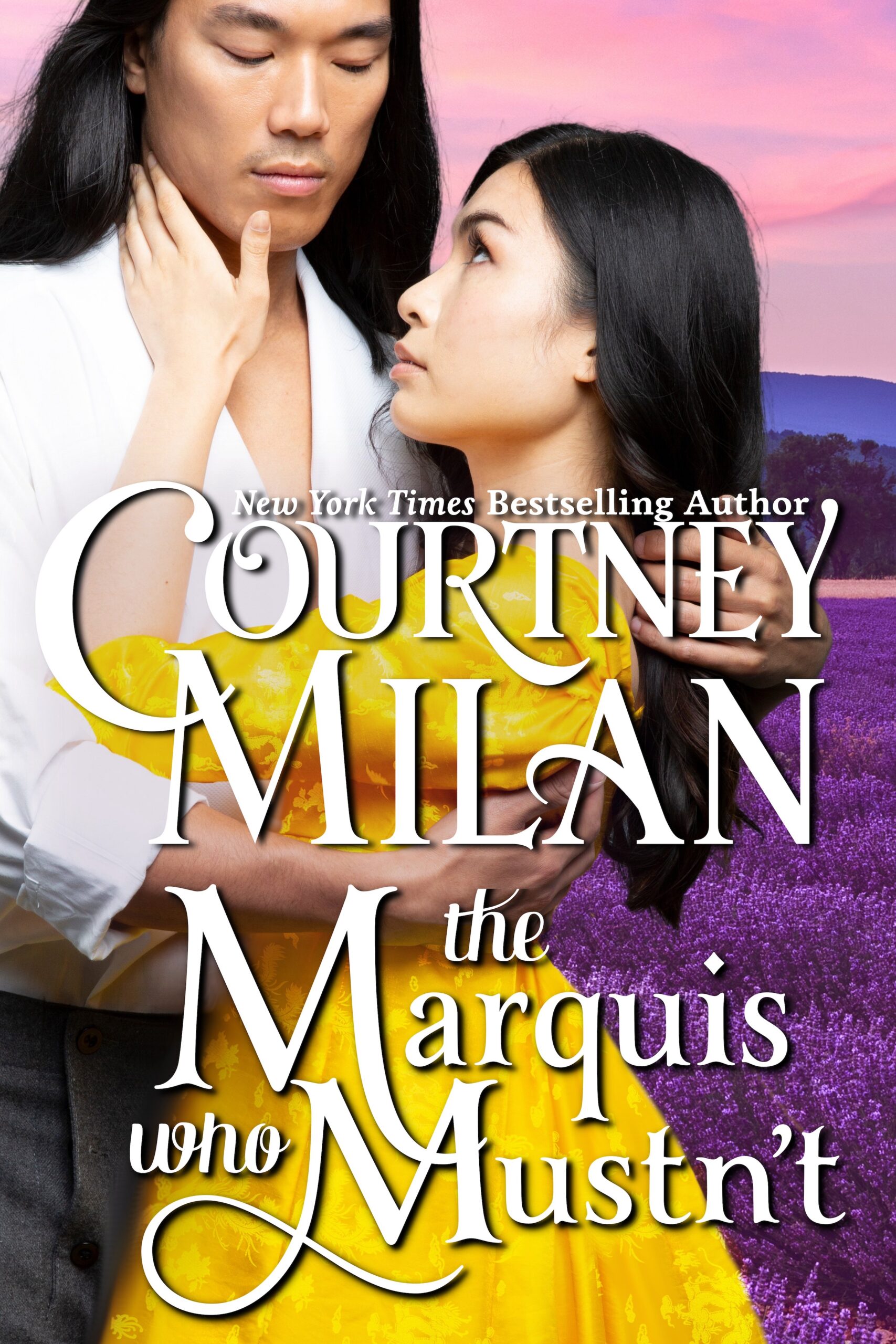

The Marquis who Mustn’t

Buy it

ebook: amazon | apple | b & n | kobo | googleprint: amazon | b & n | bookshop | ripped bodice

Read More

about the book | excerpt | code name | content notesout October 17, 2023

One good fraud deserves another...

Miss Naomi Kwan has spent years wanting to take ambulance classes so that she can save lives. But when she tries to register, she’s told she needs permission from the man in charge of her. It would be incredibly wrong to claim that the tall, taciturn Chinese nobleman she just met is her fiancé, but Naomi is desperate, and desperate times call for fake engagements. To her unending surprise, Liu Ji Kai goes along with her ruse.

It’s not that Kai is nice. He’s in Wedgeford to practice his family business, and there’s no room for “nice” when you’re out to steal a fortune. It’s not that the engagement is convenient; a fake fiancée winding herself into his life and his heart is suboptimal when he plans to commit fraud and flee the country.

His reason is simple: Kai and Naomi were betrothed as children. He may have disappeared for twenty years, but their engagement isn’t actually fake. It’s the only truth he’s telling.

The Wedgeford Trials Reading Order

1. The Duke Who Didn’t | 2. The Marquis who Mustn’t | 3. The Earl who Isn’t

Awards

- A New York Times Best Romance of 2023

Reviews

“THE MARQUIS WHO MUSTN’T takes up a foundational romance structure — the hero with a secret, and the heroine who’s getting too close to unearthing it — and shines such a blinding light on it that the whole architecture permanently shifts.”

—The New York Times

“What I appreciate most about Courtney Milan is that she makes every book fresh. Common themes run through her work but I never feel like I’m reading the same thing with a new cover. Milan always provides something new for the reader to geek out over.”

—Smart Bitches

Code Name

The code name for this book is POTTERY FRAUD, for very obvious reasons.

Excerpt

Dover, Kent

England. 1892.

Naomi Kwan was late, and it was all Mr. Peng’s fault. She had never met him, but already she resented his ill timing with a bitter, irrational passion.

“No,” she muttered under her breath as she marched briskly down the Dover street, dodging passers-by and window-gawkers alike, wrapping her shawl tightly around her shoulders. “A bitter, rational passion. Get it right, Naomi.”

Naomi had spent the early months of this winter running family errands in Dover precisely so that nobody would ask questions when the time arose. Questions lead to intrusion; intrusion lead to objection. And the objections were irrational. Not Naomi.

Last year, Naomi had made the mistake of asking for permission to take the ambulance class again. It had been the fourth year she had asked, and the fourth time she was rebuffed.

“So,” her mother had said, after she’d asked last year, “how would this work? You would go into Dover, into a class of women—”

“The class,” Naomi had been forced to tell her, “is coeducational.”

Storm clouds had begun to gather. “You would spend hours in their company. They would talk to you alone?”

Naomi had made herself take a deep breath before continuing. “I work in an inn,” she had pointed out. “I speak with men every day. I am not a fancy lady in need of a chaperone.”

“Chaperones are not the worry,” her father had put in. “Protection is. When you are here, your family is always nearby. But we couldn’t spare anyone to go along with you.”

She had been able to feel her dreams falling apart. “It is a coeducational class,” she had argued. “There will be women and men present. It is held in broad daylight. Nobody is going to assault me with a dozen other people present.”

Her parents had exchanged glances that spoke of an entire conversation from which Naomi was excluded. Then her mother had shaken her head.

“I know you want this,” she had said slowly.

Want? It had felt like a need. Everything Naomi did was because of other people. She worked in the inn because her parents owned it. She was a good cook because people needed to be fed. She’d endured years of people telling her, in various tones of voice, how very much like her mother she was.

The older Naomi grew, the more she watched her mother take fright over a course taught in Dover, the less like a compliment that comparison sounded.

The ambulance class was the first thing Naomi had wanted for no other reason than that she wanted it for herself.

“You wouldn’t want to disrupt all our schedules so close to the Trials, would you?” her father had asked.

“I wasn’t asking for that. I just want to take the course.”

“Maybe next year,” her mother had said.

It had been too many years of next year and not now. Naomi had grown from a young lady into an adult. That was the moment when she realized that age had nothing to do with their rejection. They simply did not want her to do it at all, at any age, for any reason.

They were neither the screaming sort of family nor the arguing sort of family. But that only meant that if Naomi let out the shriek that was building inside her, she would instantly lose the argument they were pretending not to have.

“Next year,” she had said in response. It had not been a surrender, although they had thought of it that way. It had been a promise to herself.

The memory of her parents’ relieved smiles when she gave way was seared into her being. She had learned her lesson. She would never again give them the chance to say no.

This year she had planned her approach with the precision of a military officer. She knew when to leave her home. She had scouted the way to the building a few weeks back. She’d mentioned not a word about the class to anyone except her best friend.

Instead, this morning, with the opening of registration upon her, she’d looked at the list they had on the door—salt, dried herring—and she’d offered to go in to Dover, do the shopping, get a newspaper…

Her father had brightened.

“How perfect that you’re planning to go to Dover!” He held up a piece of paper. “A letter from Madame Lee arrived yesterday. Mr. Peng’s brother’s nephew’s uncle’s grandson…” He read all this off the paper, an amused look on his face. “Also apparently called Peng, but he uses a different character. He is coming on the Dover ferry this morning at ten. He speaks very little English. Since you’re going in, you can meet him at the docks and make sure he gets on the London train.”

Naomi had tried not to grimace. Registration for the class also began at ten, and the advertisement had been clear that spots were limited. What was Naomi to say? I can’t do that; it interferes with my secret agenda?

She’d given her father a normal smile, one that held not one hint of her deep annoyance. “Of course I’ll find him!”

Of course Mr. Peng’s distant relation had not been on the ten o’clock ferry. Naomi had waited with increasing anxiety, hopping from foot to foot to stay warm in the winter winds off the sea as passengers disembarked. The throngs swelled around her, then thinned. Still there was no sign of anyone who could be Mr. Peng. She’d looked hastily around the docks in hopes that he’d somehow slipped by her. Meanwhile, with every passing minute, she wondered if the class slots had been filled. Would they be claimed all at once?

She had to believe the answer was no.

She had made her way from the docks to the train station, asking in every shop she passed if anyone had seen a confused man from China.

Nobody had. She’d searched the train platform. Passengers had been milling about, freshly arrived from London. For a second, she’d thought she caught a glimpse of an Asian face, but the man had walked away with a certainty to his stride, and she chalked it up to error.

The sun had been cold and bright. Clouds had blown past too swiftly to shade the streets for more than a minute or so. And over Naomi’s increasingly desperate search, the silhouette of Dover Castle had loomed in grim reminder. Time was slipping away.

The last flurry of passengers found luggage. Porters disappeared, leaving the platform empty and smelling of coal dust. And that was the moment when Naomi had decided to do something very unkind: She had decided to give up on Mr. Peng.

Now, with the advertisement nervously clutched in her hand, she was walking as swiftly as she could to her destination, dodging dogs in the gutter and ice on the pavement. Curse young Mr. Peng. Curse his inability to get off a ferry! If the spots were filled by the time she arrived…

She had read the advertisement so many times that it was beginning to come apart at the folds. Not that it mattered; Naomi had the words memorized. Ambulance classes taught by the esteemed Dr. Hobert from London, to be conducted once per month, three months in a row, from two to four p.m. on the third Thursday of every month beginning in February. Test and certification to follow. Payments will be received and enrollment allowed on personal application at 13 Bulwark St, from ten a.m. until two p.m., on the Tuesday one week prior to the start of the first class. Registration limited to the first fourteen applicants. No refunds will be allowed.

She was not being selfish, Naomi told herself as she marched down the street. She was simply not her mother, to constantly care about others at the expense of herself. This was the year when Naomi took control of her own destiny and became her own person.

She arrived at 13 Bulwark Street shortly after eleven and exhaled, squaring her shoulders.

But as she did, she caught sight of a man. He was coming out of a tailor’s shop, of all things. He was tall and not particularly handsome, and whatever passable looks he had were ruined by a stern face scowling at the world.

But he was Chinese. It wasn’t just the low bridge of his nose and the lids of his eyes that gave him away. It was his hair, dark and long, braided into the queue that signified obedience to the Emperor of China. He had also not been in China for many years. Instead of shaving the hair on his crown, the way men did in China, he’d grown it out. That, too, was common for Chinese men who wore a queue: that bald crown marked one out in a crowd.

There was a craggy look to him, like someone had stolen the face of a cliff and pretended it was a man. He was—she had already noted this, but it seemed overwhelming—tall. He was so tall it almost felt offensive.

Maybe Naomi was offended because this man was almost certainly the young, misdirected Mr. Peng, come to thwart Naomi from class registration one final time.

Their eyes met across an expanse of pavement. For a long, cold moment, they looked at each other as if mutually taken aback.

Perhaps she was imagining the surprise on his face due to the intensity of her own feelings. But Naomi had no time to waste collecting hapless semi-relations of neighbors. Especially ones who lacked the sense to wait around the ferry dock to be collected like a reasonable person ought. Naomi had been pushed around, putting off her own desires for years.

She was done with it. If Mr. Peng needed her help, he could until after registration.

The man blew out a breath and approached her first, stopping a pace from her with a bow of his head that indicated the barest minimum of respect.

He could give her more than that. She was doing him a favor.

“Mr. Peng.” Naomi addressed him in Cantonese, and despite all her annoyance, tried to give him her brightest smile. “I’m so glad I found you. My father sent me to greet you at the ferry, but as I’m sure you noticed, we missed one another there.”

“Mm.” He frowned. “Ah?”

“No need for apologies!” There was no time for them, either. “If you wouldn’t mind waiting, I must duck into this establishment. I’ll take you to Wedgeford after.”

His nose wrinkled. “There is some confusion.”

She didn’t have time for his confusion, but she was going to have to manage it nonetheless. He’d likely been lost in Dover, unable to read street signs or ask for directions. “If you’d rather not be left behind, come in with me. It’ll just be one short moment.”

“I believe—”

There was even less time for his beliefs. “Right, then!” Naomi smiled at him cheerily and hoped that would make up for the rudeness of her interruption. “In we go!” She turned her back on him and marched away, hoping that he would at least have the sense to follow.

The interior of the building was almost as cold as it was outside, and much more musty. Signs pointed the way toward registration.

Behind her, she heard footsteps. “Miss,” he called behind her in Cantonese, “please understand—”

“I will understand anything you like,” she called over her shoulder, “in a few moments. After I’m finished. Please.”

He let out an audible, frustrated sigh.

She held hers in. She was helping him. She’d take the time to apologize and coddle his affronted feelings after she registered for classes. Another paper sign pasted to the wall directed Naomi up a flight of stairs, down a corridor, then into a room where two men sat at a desk, conversing with one another.

She practically ran up to them. “Tell me I’m not too late! Are there still spots available for the ambulance class?”

She could hear the soft sound of Mr. Peng’s footsteps following her into the room.

The two men looked up at her from their seats. There was a long, long pause, in which they studied her, before looking down at the paper in front of them.

Ambulance class registration rolls. A number proceeded each of the names on the list. There were twelve enrollees. Naomi almost sagged with relief. Good. She wasn’t too late.

“I…see.” The man bit his lip and glanced behind her. “You’re registering for the class?”

She glanced behind her to see Mr. Peng. He was now glowering at her, arms folded, his long frame leaned against the wall nearest the door. He could scowl all he liked.

She turned to smile brightly at the men. “Yes. I am.”

Once again, the two men exchanged glances.

“I think she’s from Wedgeford,” one man whispered to the other in a too-loud voice.

“Of course she’s from Wedgeford, you perambulating haystack,” the other replied. “She’s Chinese.”

Naomi was half-Japanese, half-Chinese, but she rarely enjoyed going into the finer details of her heritage with strangers.

“I must tell you,” said the first man, whose pale, excessive hair did in fact resemble a haystack, “the course will be conducted entirely in English.”

“Excellent.” Naomi did her very best not to roll her eyes at the idea that she might have expected instruction in the southeast of England to be conducted in some other language. “That’s my native tongue. We speak it in Wedgeford.” Among other languages. “Please put me down as attendee number thirteen. I’m Miss Naomi Kwan. I’ll be happy to spell it for you.”

Behind her, she sensed Mr. Peng stirring. She did not react.

“Miss—Kwan, did you say?” The man in front of her pronounced it with a hard K and an exceptionally odd sounding vowel.

Now was not the time to quibble about details. “Yes.”

“Are you certain you want to take an ambulance class?”

Why did everyone ask that question?

“I’ve wanted to take one since I was seventeen.” She looked the man in the eye. “It started at the Wedgeford Trials. There are always so many visitors, and—”

“I know about the Trials.” He waved a hand.

“One woman gashed her arm open on a bit of unfinished metal. While she was bleeding, a man rushed in. He had a little bottle of carbolic acid and some bandages in his pocket. While everyone was screaming, he cleaned the wound, stopped the bleeding, and saved the day.”

Naomi had watched nearby, first in horror at the blood, and then with the sudden realization that she wanted to be like that man. She didn’t want to be the person who stood around watching and worrying; she wanted be the one who took action, the person who knew what to do.

“When he’d finished, someone asked him how he acted so quickly. The man laughed and said, ‘well, if you want to know what to do with carbolic acid, you should take an ambulance class.’ That’s me.” Naomi put a hand to her chest. “I want to be a woman who knows what to do with carbolic acid.”

There. That was her best pitch.

The two men exchanged looks as if she’d somehow missed the entire point.

“Miss K…G…” The haystack stopped as if he was trying to remember her name. It was one syllable, but he didn’t seem like he could do it. “Miss,” he finally said, “I meant it more like this. Ambulance classes aren’t for everyone.”

“They aren’t? It’s just to learn how to take care of people before a doctor arrives, isn’t it?”

“Yes, but… Miss.” He emphasized that syllable. “When it comes to unmarried women, we try to…ah, take a man’s view on things. Not all men want a wife who has touched other people.”

Naomi blinked. “Touched… You mean, touched, as in, to apply bandages?”

He tapped the dry end of his pen against his other wrist. “I say this for your own good. If a maiden is too eager for that sort of thing, it could hurt her prospects. And there’s already the matter of your race to think of.”

Naomi grimaced. “How does that play in?”

“All the more reason that people might think you fast,” the man told her. “We take a ‘first, do no harm’ approach to these things. We couldn’t possibly let you take this class without permission.”

“Permission!” Naomi could feel the bottom of her stomach drop clear to the ground two flights of stairs below. “From whom?”

“Your father, I suppose,” the man said with a shrug. “He’s the one that will have you on his hands if you never do marry. Bring him back and we’ll see about the registration.”

Five years Naomi been waiting. Five years, only to be thwarted by a bureaucrat who was worried about her chances at marriage? Even if she could return to Wedgeford—and it was hours away by foot—and convince her father to come back, it would do no good. By the time she returned, the last two spots would be taken.

Naomi had spent years hearing aunties tut about the plainness of her features and her unfortunate resemblance to a dumpling. She’d long ago decided she was not going to be left on her father’s hands like an unwanted package. She would be left to her own devices. She would want herself, even if nobody else did.

She was being denied the one thing she wanted for a reason she knew from personal experience was entirely irrelevant.

Or it would be if she let them deny her. The entire point of taking ambulance classes was that Naomi refused to be the kind of person who just let bad things happen. She no longer intended to sit by and watch. When action was needed, she wanted to be the one to take it.

That meant she had to fight for the class.

“That’s all you need? Permission?”

“And payment, of course.”

She looked around the room, trying to figure out a solution. There had to be something she could say, something she could do. Maybe she could leave and forge a letter from her father? No, they knew she was from Wedgeford: if she came back in a few minutes with such a letter, they’d know she was lying.

Maybe…

Her eyes fell on the man who had accompanied her in. He was watching her with a strangely intense expression. No doubt he was annoyed by the entire thing. She couldn’t blame him.

She hadn’t introduced herself properly, hadn’t asked him a thing about himself or his journey. She’d dragged him up two flights of stairs just so he could watch white men tell her no. Not that he would understand what they were saying, but body language was hard to miss. She would be discontented if she were him, too.

“Right.” She swallowed. “Permission. You need permission.”

An idea coalesced in Naomi’s head. It was something she could scarcely even let herself think.

“That’s what I said, isn’t it?”

Mr. Peng the Miserable returned Naomi’s gaze as that awful, no-good thought presented itself. It was deceitful. It was terrible, and Naomi wasn’t usually a terrible person.

In the moment, though…it also made sense.

And so the next words out of her mouth were this: “This man is my fiancé. He’ll give permission.”

She was shocked into silence at her own mendaciousness. She’d just lied. Brazenly. Without forethought. If anyone found out…

But who was going to find out? Young Mr. Peng spoke no English; he could hardly correct her.

The men turned to look at Mr. Peng; he simply blinked at them, looking back without a change of expression.

“You’re her fiancé?” one of the men questioned.

“Just nod,” she encouraged him in Cantonese. “They asked if you were originally from China.”

Naomi was going to be reincarnated as a toad. She was going to have to be extremely nice to poor Mr. Peng for using him in this egregious fashion—

“Yes,” the man said in an English that had a flat, strange accent, one she could not seem to place. He took a few steps to stand at her side. He held out his hand as if this were a business meeting. “Liu Ji Kai. I’m Naomi Kwan’s fiancé.”

For one infinite, stretching moment, Naomi had no idea what was happening. Then reality penetrated through her shock. The floor did not move. The walls did not shake. The ceiling did not collapse. It only felt like all of those things happened, like Naomi was standing in the midst of rubble.

This man was not Mr. Peng. He did in fact speak English. He knew precisely what she had said.

And for some unaccountable reason, Mr. Liu was pretending to be engaged to a perfect stranger.